Nautilus

Some Brains Switch Gears Better Than Others

We’re bombarded with information every instant of our waking lives. The loud kabloom in the other room that suggests the family cat knocked a book off the shelf. The street scene that streams through the window, bringing us back to a summer in our youth, and eliciting a feeling of time passing too quickly.

The cat with the book is something we might recognize in a split second, while the thought about the street scene and its implications for the present will likely require more interpretation of context and meaning. These modes of thought are often described as fast and slow modes of thinking, according to an idea popularized by the late Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman.

Fast and slow thinking matter for switching tasks and coordinating activity. But how do we shift from one kind of thinking to another—and are some of us better at this shift than others?

These were the questions that Linden Parkes, an assistant professor of psychiatry at Rutgers Health, and her colleagues recently set out to answer. The team analyzed brain imaging data from 960 people, mapping the connections between neurons to model how information flowed across different regions of their brains. While most models of the brain assume that all regions operate on the same internal clock, what they found is that the brain is not a single-speed conveyor belt and these regions run at many different speeds.

Read more: “Yes, You’re Irrational, and Yes, That’s OK”

They also found that the distribution of timescales across the cortex—the brain’s outer layer, responsible for higher order functions like thought, memory, language, and consciousness—is critical to how we switch between different modes of thinking and varies widely from person to person. They published their results in Nature Communications.

“We found that differences in how the brain processes information at different speeds help explain why people vary in their cognitive abilities,” explained Parkes in a statement. “Our work highlights a fundamental link between the brain’s white-matter connectivity and its local computational properties. People whose brain wiring is better matched to the way different regions handle fast and slow information tend to show higher cognitive capacity.”

The patterns they found also matched real underlying biology: They were associated with specific genetic, molecular, and cellular signatures found in the different brain regions. They found these patterns not just in humans, but in mice as well.

The researchers now want to take the findings into the realm of psychiatry, examining how connectivity patterns may be altered in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression.

Life is lived at many tempos and the healthiest, most nimble brains seem to have an intrinsic sense of when to change gears. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Vitaly_Vision / Shutterstock

Milky Way’s Twin Causes Rethink of Galactic Evolution

Just like us, galaxies typically go through an awkward period during their adolescence. Recent research found that young galaxies collide and merge with other galaxies, developing clumpy, asymmetric “battle scars” and bursts of stellar activity. It takes billions and billions of years for a galaxy to settle and mature into the majestic spiral-armed formations we’re familiar with.

Or so we thought.

Astronomers Rashi Jain and Yogesh Wadadekar were recently surprised to find a relatively young galaxy in pristine condition, spiral arms and all. Using deep imaging from the James Webb Space Telescope, they observed a galaxy bearing a striking resemblance to our 13.6-billion-year-old Milky Way, but one that formed only 1.5 billion years after the Big Bang, when the universe was one-tenth its current age. They named the galaxy “Alaknanda” after one of the two headstreams of the Ganges River in India (the other, Mandakini, is the Hindi word for Milky Way). They published their findings in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

A mature galaxy like ours has what’s called a “grand-design” spiral, or two massive arms swirling outward from the center that astronomers long believed needed billions of years to accrete enough material. Alaknanda appears to have achieved this feat in record time.

Read more: “Star Siblings Tell Tales of Galactic Chaos”

“Alaknanda has the structural maturity we associate with galaxies that are billions of years older,” Jain explained in a statement. “Finding such a well-organized spiral disk at this epoch tells us that the physical processes driving galaxy formation—gas accretion, disk settling, and possibly the development of spiral density waves—can operate far more efficiently than current models predict. It’s forcing us to rethink our theoretical framework.”

It’s not just Alaknanda’s shape that raised eyebrows, but its productivity as well. The precocious galaxy produces stars 20 times faster than the Milky Way, adding the equivalent of 60 suns each year. The discovery is changing what we know about how galaxies evolve and shedding light on what the early universe was like.

“Alaknanda reveals that the early universe was capable of far more rapid galaxy assembly than we anticipated,” Wadadekar said. “Somehow, this galaxy managed to pull together 10 billion solar masses of stars and organize them into a beautiful spiral disk in just a few hundred million years. That’s extraordinarily fast by cosmic standards, and it compels astronomers to rethink how galaxies form.” ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: NASA/ESA/CSA, I. Labbe/R. Bezanson/Alyssa Pagan (STScI), Rashi Jain/Yogesh Wadadekar (NCRA-TIFR)

This Is the Difference Between Child Prodigies and Late Bloomers

What produces talent? It’s an age-old question. We all remember the early prodigies. Take the brilliant composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who began composing at age 5 and wrote his first opera at 12, or mathematician Blaise Pascal, who crafted a significant mathematical treatise by 16.

For decades, scientists have reported that youthful success and narrowly focused practice leads to peak performance later in life. The earlier one begins, and the more hours of practice, the better. But a team of scientists from Germany, Austria, and the United States recently noticed that most of this research failed to take exceptional late bloomers into account. We’ve all heard their stories: Scientist John Goodenough, for instance, won a Nobel Prize in chemistry at the ripe old age of 97.

To get a better handle on the relationship between peak performance in youth and in adulthood, and the factors underlying the highest levels of human achievement, the researchers recently reviewed newly available datasets covering 34,000 adult international top performers in classical music, Olympic sports, and chess as well as Nobelists. Their findings, published in the journal Science, should give heart to late bloomers and discipline dabblers the world over.

The early prodigies and the adult standouts, they found, were generally two totally distinct groups with little overlap. Those who peaked at a young age tended to narrowly focus on a single talent and engage in disciplined practice, but exceptional adults typically reached their peak more gradually, performing less well early on, and tended to develop talent in many different areas of interest. The researchers also found that among the most talented adults, better performance in one’s youth actually predicted worse peak performance later.

Read more: “Not All Practice Makes Perfect”

The patterns were remarkably similar across disciplines: Only 10 percent of the world’s top-10 youth chess players and top-10 adult players were the same individuals. A similar number crossed over when it came to top-tier high school and university students as well as international-level youth athletes and adult athletes. “The similar developmental pattern of world-class performers across different domains suggests widespread, if not universal, principles underlying the acquisition of exceptional human performance,” the authors wrote in the study.

They provided a few explanations for their findings. Trying out many things helps people figure out where their true talents lie and builds flexible thinking and learning skills and creative problem-solving that pay off later. Early specialization can also lead to burnout. Ultimately, the findings suggest that the way we currently train for elite performance may miss the mark: Most institutions choose kids who show early promise and then push them to practice their craft repeatedly. This kind of intense specialization can produce very gifted teenagers but may miss the kinds of achievers who will become outstanding adults.

What talent scouts should really look for, the authors advise: above-average early performance, steady progress, and serious engagement in multiple fields before the focus narrows. In other words, exploration, patience, and breadth may win the day and produce the greatest genius.

So if you haven’t hit your stride quite yet, take solace. It’s a brand new year and you have your whole life ahead of you, whether you’ve clocked 12 years on this planet, or are about to hit 92. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Blue Planet Earth / Shutterstock

A Martian Milestone Captures a Mysterious Dark Spot

You’re looking at a dark, volcanic stretch of Mars, known as Syrtis Major, that spans some 800 miles in diameter. This image was captured with color filters to highlight the gritty details of these sand dunes and plains, some of the oldest ever discovered on the Red Planet. Syrtis Major is the Greek name for the Gulf of Sirte on the north African coast, which also has a triangle-like shape, and it translates to “the great sand bank.”

This is the 100,000th image taken by the HiRISE camera, or High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, aboard NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. It was shot in October and released last month. Such a specific view will help pinpoint the origins of the sand that’s whipped around by wind and built up into dunes, which may emerge in part from the area’s dark, weathered basalt rocks.

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter launched in 2005 to hunt for hints that water once flowed for long enough on the Red Planet to sustain life—a mystery that remains unsolved. Over the past two decades, HiRISE has offered detailed peeks at hundreds of spots on the Martian surface. In fact, the sophisticated camera can pick up on surface features as small as a kitchen table.

Read more: “The Moss That Could Terraform Mars”

All of which has yielded crisp views of many different Martian scenes, including the remnants of gaseous eruptions and impact craters. These images enable scientists to trace how the surface transforms over time and seek out possible landing spots and ice deposits to aid future human missions.

HiRISE snapped this specific site thanks to a recommendation from a Colorado high school student—anyone can propose a spot on Mars for the team to check out on this website. “One hundred thousand images just like this one have made Mars more familiar and accessible for everyone,” said Shane Byrne, HiRISE principal investigator, in a statement.

Now, you can help the HiRISE team decide where to point its powerful camera and help illuminate Mars’ past—and future. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: NASA/JPL-Caltech/University of Arizona

Elephant Seals Almost Always Return Home to Give Birth

When a young adult leaves home to work or study, there’s a good chance they’ll settle into life in a new locale. A Pew Research Center survey found only 18 percent of United States adults between the ages of 25 and 34 live in their parents’ homes, despite the potential advantages of familiarity and lower costs. In contrast, for many species, females return to their homelands to reproduce. Such “natal philopatry” has been recorded in animals as diverse as sparrows and turtles. Now, a study published in Oecologia shows that elephant seals also return to their birthplaces—again and again.

Researchers from the University of California, Santa Cruz, used 20 years of mark-recapture data to track nesting of Northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris) in a colony at Año Nuevo State Park in the Golden State. Previous unpublished research indicated that about 10 percent of females dispersed from Año Nuevo to breed elsewhere, while the majority returned to the same general coastline. By mapping returning female locations, the researchers hoped to determine the specificity of their loyalty to their birth sites.

Distances between birth sites and pupping sites were analyzed for 124 mother-pup pairs at Año Nuevo from 2000 to 2023. The results demonstrated that females bore their pups significantly closer to their own birth site than random chance would dictate. On average, a female gave birth 1,296 feet from where she was born, and a quarter of the time within just 407 feet—a bit more than the length of a football field. While that may sound like a lot, consider that these females are migrating to the nesting beaches from thousands of miles away.

Read more: “A Leopard Seal Mother’s Love Transcends Death”

“It is already remarkable that northern elephant seals—a species that can travel more than 12,000 miles in a single year—can navigate back to the same colony where they were born. We found that this precision continues within the colony, with underlying drivers of site selection creating a surprisingly organized breeding structure,” explains Bella Garfield, lead author and now a marine science grad student at the University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth.

Also, in their future rounds of reproduction, females tended to return close to the spots where they had their pups. So, their natal philopatry carried across years of their lives, although longer intervals between pupping corresponded with nesting further away. “This fine-scale philopatry suggests a generational context for where seals choose to pup, with implications for genetic dispersal within the colony,” Garfield adds.

Returning to the same site to breed confers a risk of inbreeding with relatives, with the consequent genetic liabilities of lower diversity. Given that Northern elephant seals recovered from near extinction, their tendency to return to natal sites may limit the outcrossing needed to restore genetic diversity.

However, their loyalty to their birth sites may increase the chance of locating a mate as well as confer the advantage of already being familiar with environmental conditions at the site. “Our results establish a baseline for breeding patterns at Año Nuevo that can be revisited to understand how environmental change reshapes colony structure over time,” says Garfield. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Tiny Turkey / Shutterstock

X-rays Were a Life-Saving Accident

The groundbreaking finding that enables doctors to peek inside our bodies and astronomers to probe the mysteries of space was announced on this day, 129 years ago.

Wilhelm Röntgen, a German physicist, accidentally discovered the X-ray in 1895 while tinkering in his lab. At the time, scientists were fascinated by the then-elusive dynamics of electricity. Röntgen had wondered whether streams of electrons called cathode rays—produced in charged glass containers called cathode tubes—could move through glass.

He had covered his cathode tube in heavy black cardboard, but he noticed that a green glow seeped through and projected onto a fluorescent screen in his lab. This odd phenomenon persisted even when the receiving surface was more than 6 feet away from the tube.

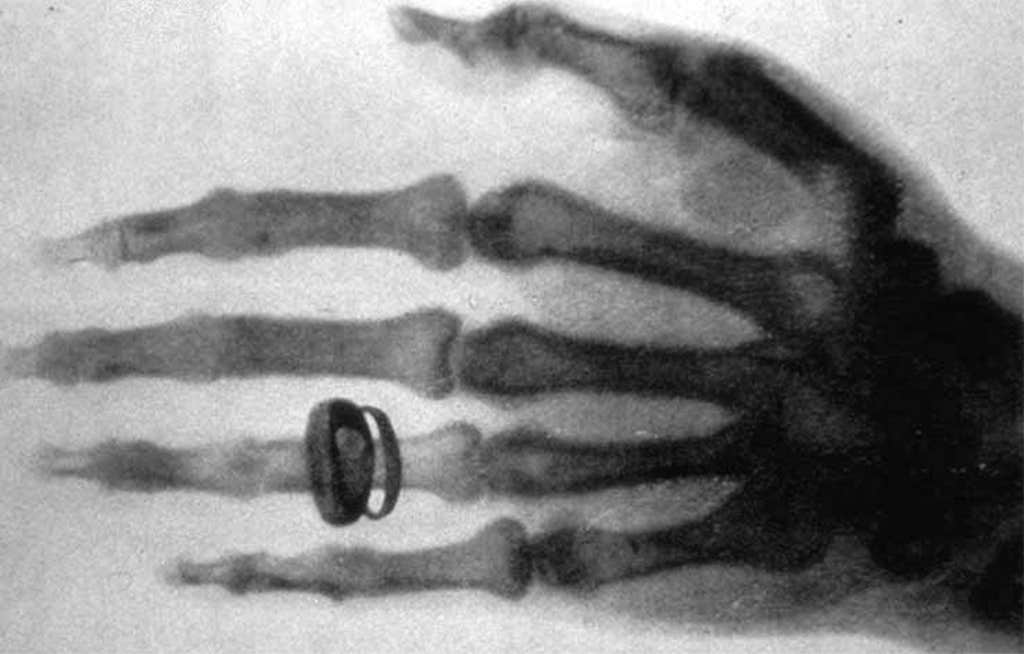

Wilhelm Röntgen/Old Moonraker/Wikimedia Commons.

Röntgen beamed the rays through items of varying thickness and observed that they showed different degrees of transparency to this light when recorded on a photographic plate. He named them X-rays, with X referring to “unknown.”

On January 5, 1896, the Austrian newspaper Die Presse broke the news of this revelation. The article “was composed hastily by the editor in a journalistic style and contained no information on the nature of the new rays,” according to a paper published in the Journal of the Belgian Society of Radiology. Two days later, however, Die Presse ran another article with more details on the finding.

Read more: “Discovering the Expected”

Not long after his initial X-ray experiments, Röntgen learned that his rays could travel through human tissue to illuminate the bones within. He captured the bones in the hand of his wife, Anna Bertha Ludwig. “I have seen my death,” she said at the time. Röntgen noticed that the skin around her bones had a fainter shadow because it was more permeable to the rays

In later experiments, German physicist Max von Laue and his students demonstrated that X-rays “are of the same electromagnetic nature as light, but differ from it only in the higher frequency of their vibration,” according to the Nobel Prize organization.

Within a year of Röntgen’s initial eureka moment, doctors in the United States and Europe incorporated the new-fangled technique into their work. In 1901, Röntgen received the inaugural Nobel prize in physics, among other awards, and several cities named streets after him. Still, he “retained the characteristic of a strikingly modest and reticent man,” the Nobel Prize organization notes. In fact, Röntgen never applied for patents and said that “his inventions and discoveries should belong to humanity. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Internet Archive Book Images / Wikimedia Commons

This Walking Ape Might Be the Earliest Human Ancestor

Whenever you take a stroll, you take advantage of a key feature that separates us from our ape relatives—bipedalism, or walking upright on two legs.

Fossils with signs of this trait can point scientists to our earliest human ancestor, or the first member of the hominin group that includes modern and extinct humans. A possible candidate for this ancient relative: Two decades ago, scientists announced the identification of Sahelanthropus tchadensis, a hominin species from around 7 million years ago—around the time when humans split from apes.

Back then, researchers had examined jaw bits, teeth, and most of a cranium from S. tchadensis, which were found in what’s now the country of Chad. More recent research has zeroed in on two pieces of forearm bones and part of a thigh bone or femur that were later identified as belonging to the same species.

Since S. tchadensis was unveiled, scientists have squabbled over the possibility that it was bipedal. Some have even questioned whether the creature was a hominin at all.

Now, analysis of limb bones from this species suggest that it could indeed walk on two legs. While the bones they observed look similar to those of chimpanzees, they found several compelling pieces of evidence of bipedalism, findings reported in Science Advances.

A team from across the United States took a close look at these bones and discovered a key indicator of bipedalism: a femoral tubercle, a bony bump on the femur where the iliofemoral ligament attaches; it’s the biggest and most powerful ligament in the human body, and links the femur to the pelvis. This feature has only been found in bipedal hominins, and it is a crucial ingredient for upright walking.

Read more: “How Posture Makes Us Human”

They also confirmed hominin-like details in the bones that were pinpointed in past studies: a twist in the femur that helps orient the legs forward, and muscles that keep the hips stable and assist in walking, standing, and running. Additionally, the femur was relatively long compared with the ulna, a bone in the forearm, another hint of bipedalism.

S. tchadensis did have shorter legs than modern humans, but its femur length wasn’t too far off from a sample taken from Australopithecus, a genus of early hominins that evolved around 4 million years ago.

Overall, the evidence suggests that “bipedalism evolved early in our lineage and from an ancestor that looked most similar to today’s chimpanzees and bonobos,” said study co-author Scott Williams, an evolutionary morphologist at New York University, in a statement.

This species “was essentially a bipedal ape that possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain,” Williams added. It seems to have spent much of its days in trees, seeking out food and safety, but was adapted to walk on the ground. S. tchadensis may offer an example of an “early form of habitual, but not obligate, bipedalism,” the authors noted in the paper, as they think bipedal behavior grew over the course of evolution before it became a more heavily utilized hominin characteristic.

Ultimately, the path toward traversing the world on two legs may have proven a marathon, not a sprint. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Didier Descouens / Wikimedia Commons

The Science Behind Better Visualizing Brain Function

One of the ongoing challenges in understanding the workings of the human brain is being able to visualize its activity in real time. Our brains are collections of nerve cells, or neurons, that receive, transform, and send signals to other cells to create thoughts, decisions, and memories. To date, researchers have illuminated the outgoing signals from nerve cells using techniques like electrophysiology but have found the incoming signals too fast and faint to capture.

Now, described in a recent paper published in Nature Methods, neuroscientists have devised a way to detect incoming chemical signals. “What we have invented here is a way of measuring information that comes into neurons from different sources, and that’s been a critical part missing from neuroscience research,” explained lead study author Kaspar Podgorski at the Allen Institute in Seattle in a statement.

Podgorski and an international team of collaborators from the United States, Germany, Italy, London, and Austria engineered variants of a protein—iGluSnFR—to record incoming brain cell signals. Nerve cell signals bridge the gap between neurons by sending chemical messengers across the gap, or synapse. The most common messenger for learning, memory, and feelings is the molecule glutamate, for which the iGluSnFR protein is a good tracking indicator.

Read more: “A New Doorway to the Brain”

By testing the performance of 70 variants of iGluSnFR in mouse brains, the researchers discovered two variants that were sensitive enough to detect even the faintest incoming neural signals. The glutamate indicators were tested in mouse models in various regions of the brain—including the neocortex, thalamus and hippocampus, and midbrain—and proved able to provide a window into information flow between neurons of various types. Coupled with existing techniques to monitor outgoing signals, the iGluSnFR variants offer a way to interpret entire through-puts of information in the brain.

“I feel like what we’re doing here is adding the connections between those neurons and by doing that, we now understand the order of the words on the pages, and what they mean,” Podgorski continued.

The scientific advance has implications for treating a range of diseases that are linked to disruptions in glutamate signaling, including Alzheimer’s, schizophrenia, and autism. Being able to visualize the activity of synapses paves the way for understanding the mechanisms underlying brain disorders and then developing drugs that restore normal synaptic function. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Juan Gaertner / Shutterstock

How to Glimpse the Prime Meteor Shower of 2026

Tonight, people in the northern hemisphere may glimpse one of the year’s most dazzling meteor showers: the Quadrantids.

This cosmic spectacle peaks annually in early January, and it’s particularly tricky to get a good look at it compared with other meteor showers. Many peak over two days, but Quadrantids are usually visible for just a few hours.

The bright streaks we see during meteor showers result from sand-sized bits of dust released from comets or asteroids, known as meteors, which barrel into air particles in our atmosphere. The collision creates heat that vaporizes meteors, producing the streaks of light that have astonished people for millennia. This glow can take on different hues depending on the chemical makeup of a meteor and its speed.

We can see a few meteor streaks each night, but highly anticipated showers like the Quadrantids occur when Earth passes through trails of dusty space rock remnants around the same time each year. The Quadrantids, which are thought to emerge from an asteroid called 2003 EH1, can look blue or yellow.

The Quadrantids peak is particularly brief because the shower consists of a skinny stream of particles that Earth cruises through at a perpendicular angle. Another viewing obstacle: The height of the shower will coincide with a supermoon, which happens when the full moon is closest to Earth in its orbit—this makes it look up to 14 percent bigger and 30 percent brighter than the year’s faintest moon.

Read more: “Before the Supermoon Showed Its Face It Flashed Us”

“The biggest enemy of enjoying a meteor shower is the full moon,” Mike Shanahan, planetarium director at Liberty Science Center in New Jersey, told The Associated Press.

Tonight, onlookers may see up to around 10 Quadrantid meteors per hour. This shower is known for its especially luminous and long-lasting fireball meteors, which emerge from relatively big bits of material.

It gets its name from Quadrans Muralis, a former constellation discovered in 1795, the spot in the sky where the meteors appear to travel from. The moniker refers to the quadrant, an early astronomical tool that people used to map out star locations.

To get a good look at the Quadrantids, NASA recommends settling down in a spot far from light pollution and lying flat on your back with your feet oriented northeast. Stay off your phone and let your eyes get accustomed to the complete darkness, a process that takes around 20 minutes. “Be patient—the show will last until dawn, so you have plenty of time to catch a glimpse,” NASA advises.

For location-specific tips on your best shot at seeing the Quadrantids, check out timeanddate.com. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: Aref Fathi / Wikimedia Commons

Everything We Thought We Knew About How Stardust Spreads Across the Cosmos Is Wrong

The elemental building blocks that made life on Earth possible may have originally come from red giant stars, but how they got here has remained something of a mystery. For decades, scientists assumed carbon, oxygen, and nitrogen were carried across the cosmos, blown by stellar winds pushing infinitesimal motes of stardust. But now, new research from a team led by Theo Khouri at Chalmers University of Technology is upending that hypothesis.

Observing the star R Doradus with instruments equipped on the Very Large Telescope in Chile, astronomers analyzed polarized light of different wavelengths reflecting off dust grains surrounding the red giant. Incredibly, this allowed them to determine both the chemical makeup and size of the tiny grains from over 180 light-years away. Using advanced computer models, they came to a surprising conclusion: The dust particles were too small to escape the star with stellar radiation alone. They published their findings in Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Read more: “How to Build a Planet from Dust”

“Dust is definitely present, and it is illuminated by the star,” study co-author Thiébaut Schirmer explained in a statement. “But it simply doesn’t provide enough force to explain what we see.”

The stellar wind hypothesis was the easiest explanation for the spread of these particles, but oftentimes, Occam’s razor gets snagged on scientific reality. Though this latest research is sending astronomers back to the drawing board, they’re far from discouraged—if anything, they’re a little enthusiastic.

“Even though the simplest explanation doesn’t work, there are exciting alternatives to explore,” study co-author Wouter Vlemmings added. “Giant convective bubbles, stellar pulsations, or dramatic episodes of dust formation could all help explain how these winds are launched.”

When it comes to the scientific method, sometimes bad news is the best news. ![]()

Enjoying Nautilus? Subscribe to our free newsletter.

Lead image: ESO/T. Schirmer/T. Khouri; ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO)